- Veterinary View Box

- Posts

- Hidden Reflux: 75% of Dogs With Respiratory Disease Have Silent Swallowing Abnormalities

Hidden Reflux: 75% of Dogs With Respiratory Disease Have Silent Swallowing Abnormalities

Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 2023

Jennifer Howard, Megan Grobman, Teresa Lever, Carol R. Reinero

Background:

Aerodigestive disorders (AeroD) are underrecognized in dogs, particularly in those with respiratory signs but no overt alimentary clinical signs. Videofluoroscopic swallow study (VFSS) offers a dynamic method to detect swallowing abnormalities, reflux, and aspiration. This study hypothesized that dogs with respiratory disease (RESP), despite no gastrointestinal symptoms, would show more VFSS abnormalities than healthy control dogs (CON), and that those with parenchymal disease would show more reflux and penetration-aspiration than those with airway disease.

Methods:

A prospective case-control study was conducted in 45 RESP and 15 CON dogs. RESP dogs underwent VFSS along with thoracic CT, tracheobronchoscopy, and bronchoalveolar lavage. VFSS included eight subjective and three objective metrics: pharyngeal constriction ratio (PCR), penetration-aspiration score (PAS), and esophageal transit time (ETT). Data were analyzed using Fisher’s exact and Mann-Whitney tests. RESP dogs were subclassified based on predominant airway or parenchymal pathology.

Results:

VFSS abnormalities were found in 75% of RESP dogs compared to 13% of CON dogs (P = .01). Pathologic PAS (≥3) occurred in 27% of RESP dogs but in none of the CON group (P = .03). RESP dogs with airway disease had significantly higher PAS than controls (P = .01). Pathologic reflux was observed in 36% of RESP and 13% of CON dogs (not statistically significant). No significant differences were found in PCR or ETT between groups. Common VFSS findings in RESP dogs included reflux, esophageal weakness, hiatal hernia, and pathologic aerophagia. Three RESP dogs with idiopathic cough (no respiratory tract abnormalities) all had VFSS abnormalities.

Limitations:

Small control group, lack of brachycephalic controls, and short VFSS cine loops may have missed intermittent events. Not all objective metrics could be evaluated in all dogs due to poor compliance or technical limitations. The RESP dogs were significantly older, though prior research suggests VFSS metrics are not age-dependent. Microaspiration could not be assessed by VFSS.

Conclusions:

AeroD are highly prevalent in dogs with respiratory disease, even in the absence of gastrointestinal symptoms. VFSS proved valuable for detecting silent swallowing abnormalities and should be included in the diagnostic workup of such dogs. RESP dogs with airway disease were especially likely to show signs of penetration or aspiration. These findings support an integrated diagnostic and therapeutic approach targeting both respiratory and alimentary tracts.

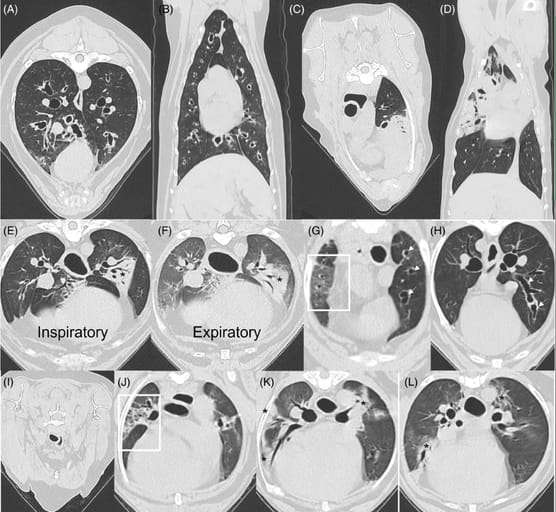

Use of thoracic computed tomography to aid in classification of final diagnosis in dogs with respiratory disease based on airway, parenchymal or mixed airway and parenchymal involvement. (A, B) Transverse and dorsal sections from a 6-year-old MC Siberian Husky with airway disease. Note the marked peribronchovascular thickening creating an appearance of peribronchial cuffing in cross-section. Bronchiectasis was noted by dilatation and lack of tapering of airways traversing to the periphery. The final diagnoses were eosinophilic bronchitis and bronchiectasis. (C, D) Transverse and dorsal sections from a 10-year-old FS Labrador retriever with parenchymal disease. Note the extensive regions of consolidation. Histology and response to immunosuppression confirmed an immune-mediated lung disease. (E, F) Paired ventilator-assisted inspiratory: expiratory breath hold transverse sections from an 11-year-old MC French bulldog with both airway and parenchymal disease substantially contributing to clinical signs. On the inspiratory series, increased peribronchovascular thickening and focal consolidation (*) are noted. On the expiratory series, the caliber of the segmental and subsegmental airways are smaller than on the inspiratory series with a corresponding loss of lung volume and presence of more global ground glass opacity because of downstream effects of bronchomalacia. The previously noted region of consolidation (*) remains present. The final diagnoses included brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome, bronchomalacia, aspiration pneumonia, and suspect pulmonary fibrosis (corresponding lesions not shown). (G, H) Transverse images from a 13-year-old FS French bulldog with predominating airway lesions and mild, focal evidence of parenchymal disease. In (G), ground glass opacification in the mid-zone of the lung (within the white box), with Hounsfield units ranging from −425 to −550. The white arrows on the right side of the figure show bronchiectatic airways. Further evidence of cylindrical bronchiectasis is seen in (H) with a lack of tapering as shown by the white arrows. Using data from the clinical picture and other advanced diagnostics, the final diagnoses were chronic bronchitis, bronchiectasis, mainstem bronchial collapse, hiatal hernia, and uncharacterized parenchymal disease. (I-L) Transverse images from a 14-year-old FS Pomeranian with predominating parenchymal disease and a lesser contribution of airway disease. In (I) taken from the expiratory series, grade II tracheal collapse is demonstrated by a 50% reduction in luminal diameter with a flattened shape. In (J), the box outlines a region of architectural distortion characterized by traction bronchiectasis/bronchiolectasis superimposed on a background of reticulation and ground glass opacity, compatible with pulmonary fibrosis. In (K) and (L), there are multifocal regions of ground glass opacity and consolidation (*). Final diagnoses were grade II tracheal collapse, grade I mainstem bronchial collapse, grade I bronchomalacia, extra-esophageal reflux, suspect pulmonary fibrosis, and uncharacterized parenchymal disease.

How did we do? |

Disclaimer: The summary generated in this email was created by an AI large language model. Therefore errors may occur. Reading the article is the best way to understand the scholarly work. The figure presented here remains the property of the publisher or author and subject to the applicable copyright agreement. It is reproduced here as an educational work. If you have any questions or concerns about the work presented here, reply to this email.