- Veterinary View Box

- Posts

- Recognizing Synovial Tumors in Dogs: New Insights on Histiocytic and Myxosarcomas

Recognizing Synovial Tumors in Dogs: New Insights on Histiocytic and Myxosarcomas

Veterinary Pathology 2024

Linden E. Craig

Background

Confusion in the terminology and classification of synovial tumors in dogs has long complicated diagnosis and treatment. This review provides an updated understanding of sarcomas arising from the synovial lining of joints—particularly histiocytic sarcomas and synovial myxosarcomas. It also revisits the debated cells of origin, clarifies diagnostic markers, and evaluates behavior and prognosis. The article emphasizes the inappropriateness of using terms like “synovial cell sarcoma” in veterinary medicine due to their misleading histogenesis.

Methods

This is a narrative review synthesizing existing literature, histological studies, immunohistochemistry, and the author’s clinical and diagnostic experience. It discusses synoviocyte types, tumor morphology, breed predispositions, diagnostic challenges, and clinical outcomes. References include studies from the veterinary pathology, oncology, and histology literature, along with unpublished data and expert observations.

Results

Two primary synovial tumors are described:

Synovial histiocytic sarcomas, likely derived from type A synoviocytes (histiocytes), express CD18, Iba-1, and sometimes E-cadherin. They often occur in joints with prior inflammation or injury and cause bony lysis. These tumors are more prevalent in Bernese Mountain Dogs, Rottweilers, and retrievers, with a median survival of 391 days—better than nonsynovial histiocytic sarcomas.

Synovial myxosarcomas, presumed to arise from type B synoviocytes, are slow-growing and locally invasive with rare lymph node metastasis. Histologically, they show sparse mesenchymal cells in a myxoid matrix. Although previously labeled “myxomas,” evidence of metastasis supports the designation “myxosarcoma.” Dogs typically present with chronic lameness and swelling; survival post-amputation is approximately 2.5 years.

The review also underscores that “synovial cell sarcoma” (a term used in human oncology for a tumor not of synovial origin) is a misnomer in dogs and should be abandoned.

Limitations

As a review article, this work does not present new primary data or a systematic meta-analysis. Some assertions rely on unpublished observations or limited case numbers. The absence of lineage-specific markers for type B synoviocytes and the reliance on frozen tissues for some immunophenotyping techniques hinder definitive conclusions regarding tumor origin.

Conclusions

Understanding the distinct behaviors and cellular origins of synovial histiocytic sarcoma and synovial myxosarcoma is essential for accurate diagnosis and prognosis in dogs. Histopathology, supported by immunohistochemistry, remains vital for differentiation. Veterinary medicine should avoid the term “synovial cell sarcoma,” reserving diagnoses for neoplasms with clear synovial histogenesis.

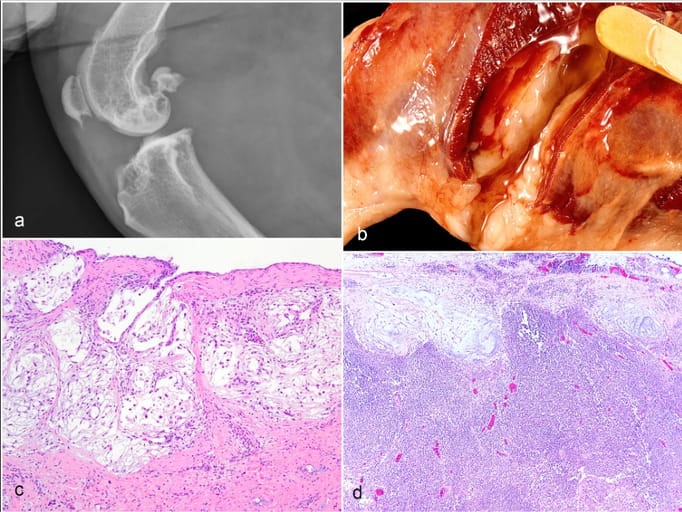

Synovial myxosarcoma, dog. (a). Radiograph of the stifle joint showing bony lysis in the distal femur, proximal tibia, and patella. (b). Periarticular pockets of clear viscous fluid surround the affected stifle. (c). The tumor consists of sparsely cellular nodules of stellate mesenchymal cells suspended in a pale basophilic to clear myxomatous matrix. Hematoxylin and eosin (HE). (d). Metastatic nodules at the periphery (subcapsular sinus) of a lymph node.

How did we do? |

Disclaimer: The summary generated in this email was created by an AI large language model. Therefore errors may occur. Reading the article is the best way to understand the scholarly work. The figure presented here remains the property of the publisher or author and subject to the applicable copyright agreement. It is reproduced here as an educational work. If you have any questions or concerns about the work presented here, reply to this email.